Welcome

to Our Site

Installations:

"Installation art is an artistic genre of three-dimensional works that are often site-specific and designed to transform the perception of a space."

The Memory of Water, Buenos Aires 2018

During my artist residency at Fundación´ace for Contemporary Art in Buenos Aires, I took a unique approach to exploring the memories associated with water. Combining intuition and archival research, I spent time by the Rio de la Plata, tracing its origins and exits. Tracing how the water moves through the city and noticing that the city is designed to face away from the river. I spent days listening to the stories of local people who live on or use the river daily. I also spent time with community groups striving to improve the river's water quality and remove the massive amount of trash accumulated along the coastlines. Based on my experiences, I created an installation piece that included the sounds of water leaving the city through various drains and entering the Rio de la Plata. I also incorporated oral stories, video work, archival images of joyful recreation on the Rio deal Plata, and excavated objects from the river itself.

My ultimate goal was to present a vision of the long-term history held within the water while highlighting the significant connection between water health and human life. Through the installation, I aimed to inspire people to reflect on their own relationship with water and how we can contribute to protecting this vital resource.

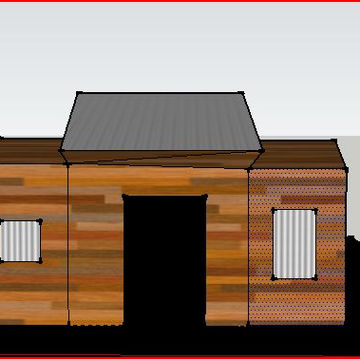

Punk Rock Bourgeoisie, 2009

Punk Rock Bourgeoisie was an immersive installation presented during Art Basel week in Miami, inspired by the painting series "Imagined Interiors". The installation explored the decadence of the material world and the neglected inner world of Western civilization, obscured by layers of social formalities. The organic-shaped structure invited visitors to navigate a maze of rooms filled with hidden secrets, doors, inverted decor, and mirrored paths, providing a unique and thought-provoking experience.